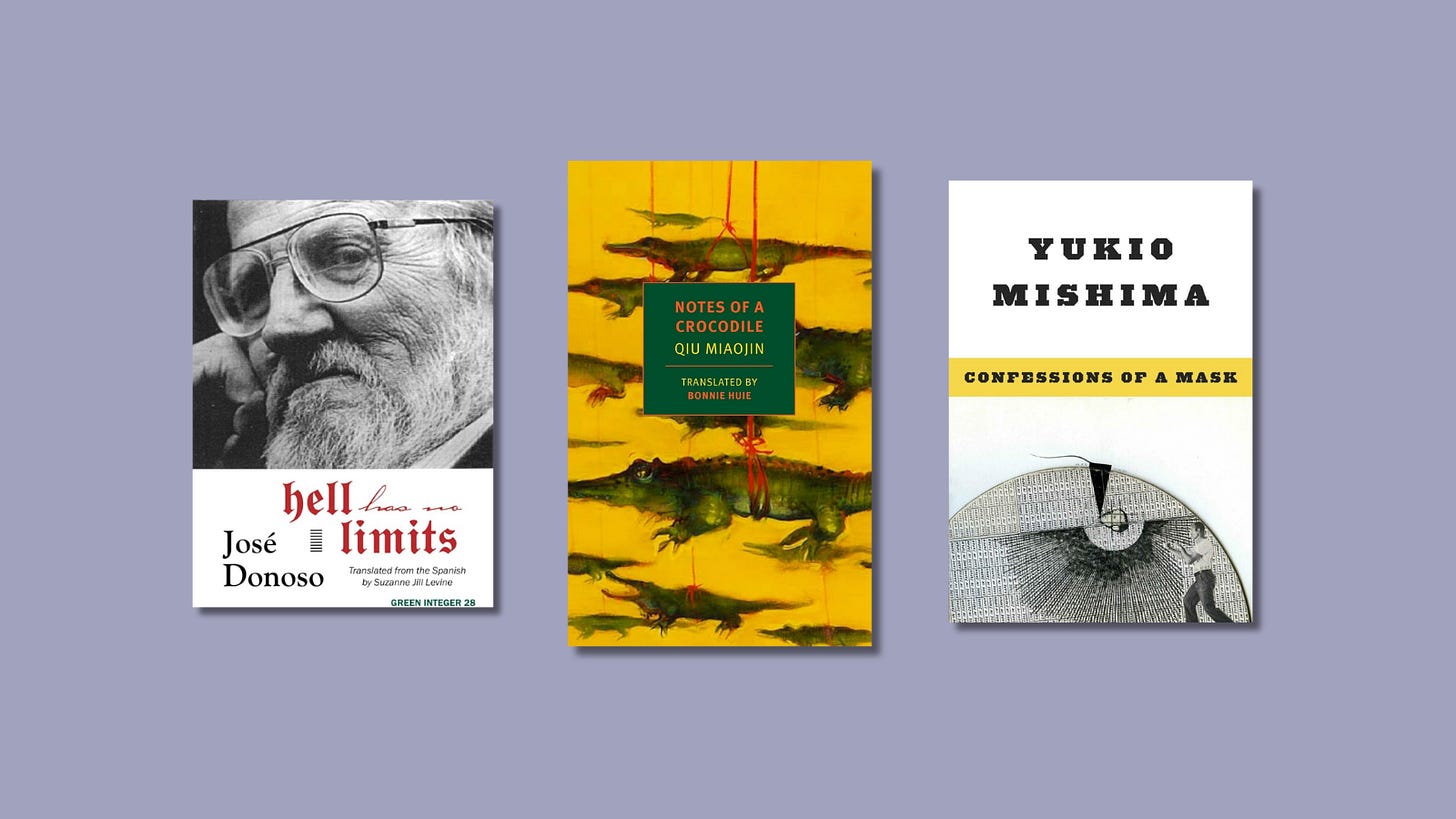

Three queer classics in translation

Recommending novels from Chile, Taiwan, and Japan

Regan’s newsletter publishes book recommendations on a theme and the occasional essay. Past newsletters have covered the 5+ club and author completionism, reading routine, women in translation, and more.

The year is winding down, and so is my third semester of grad school—!! I love being in classes and reading for classes, love figuring out what I’ll be taking in the spring; it’s all going by very quickly! This semester, a translation seminar1 introduced me to a handful of new novels and writers that I was glad to have been pushed to read, and I figured I would take the chance to recommend three favorites to you here.

I will give fair warning, though, that the three novels featured in this newsletter are far from heartwarming holiday reads; they’re heavy and dark and deal with death, abuse, suicide, etc.

But I think the translator of Notes of a Crocodile, Bonnie Huie, is incredibly convincing when she speaks about the importance of reading literature that features pain and suffering—and its net-positive impact on our collective tolerance of discomfort. In an interview for World Literature Today, she’s asked what Qiu Miaojin’s Taiwanese novel can offer US readers, and she answers:

“Americans are often said to be optimistic, and you almost certainly have to be in order to accept the terms of the economic system. Optimism has its dark side, as it invokes denial. The resulting belief system manifests itself in a popular taste for happy endings, or a narrative trajectory based on a naïve faith in just outcomes. […] Art that depicts firsthand pain and suffering is essential to freedom of thought, which is also why it offends sensibilities. Notes of a Crocodile is not about how “it gets better”; it’s about living in permanent wartime. A vicious cycle begins when you lose the ability to feel, then the ability to tolerate discomfort. Qiu handed down a book of memories that preserves these essences so that you can use them like smelling salts.”

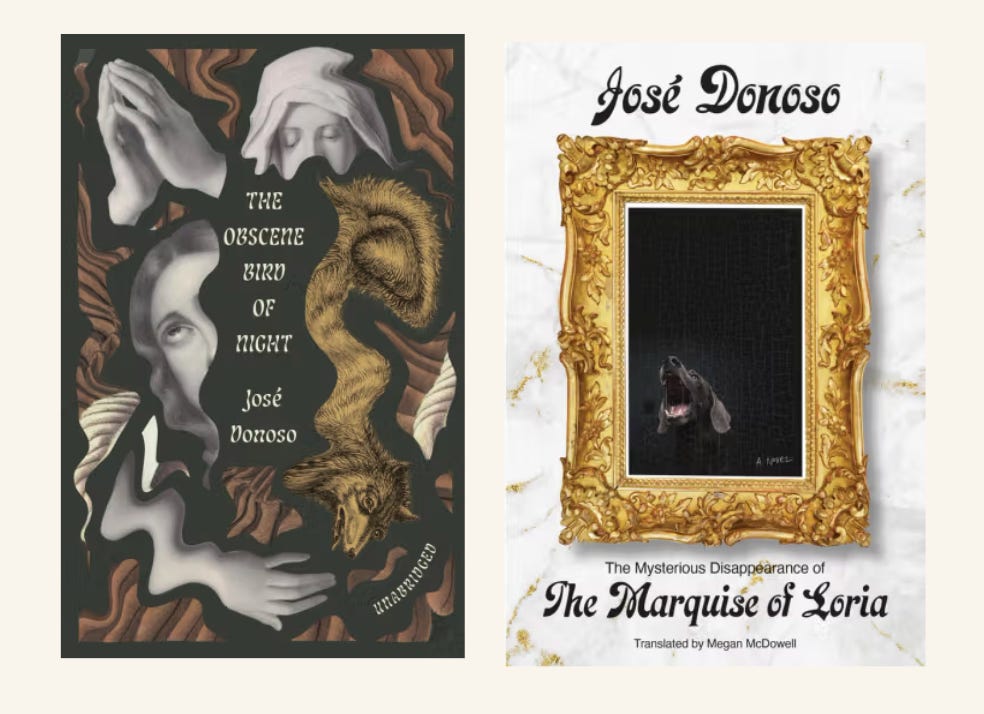

Hell Has No Limits by José Donoso, tr. Suzanne Jill Levine (Green Integer, 1966/1972)

This little book really blew me away, caught me totally off guard; I read it in one go, late into the night, despite knowing I had to wake up early the next morning. José Donoso is one of the great Latin American Boom novelists of the 60s and 70s (alongside the likes of Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, Gabriel Garcia Marquez!)—but this was my first encounter with his work.

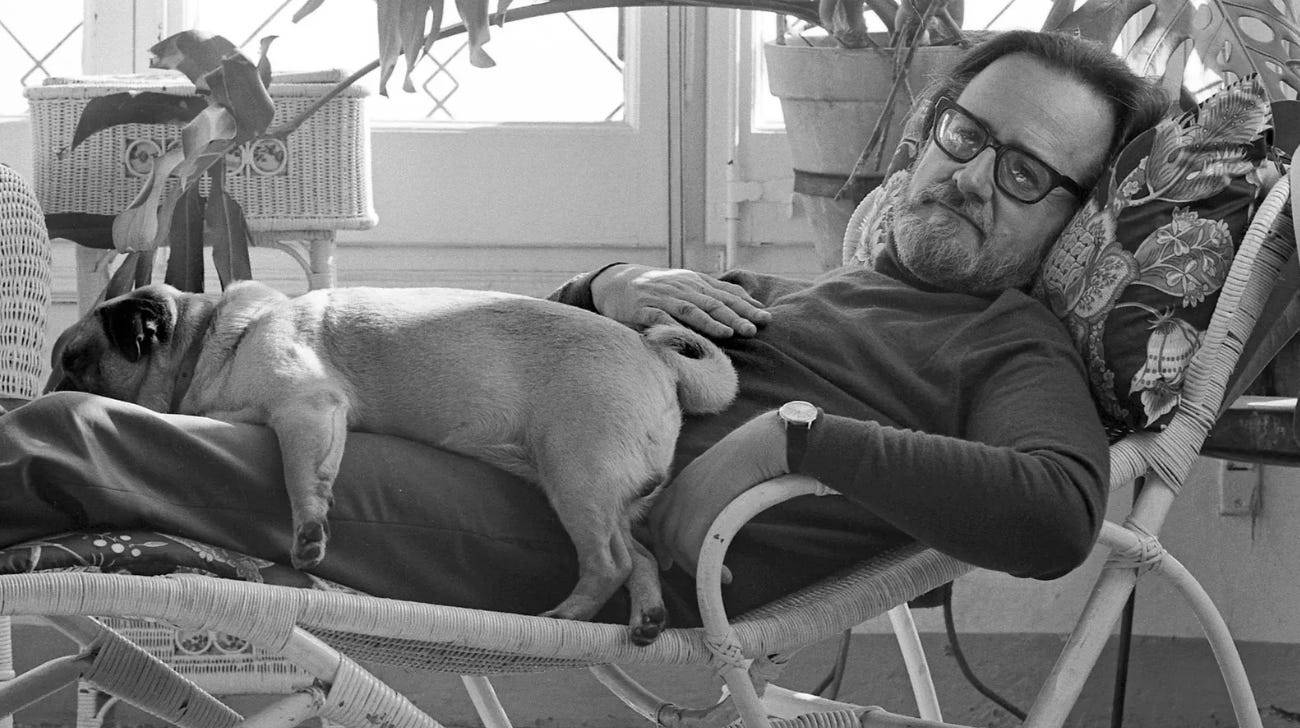

José Donoso was born and raised in Chile and wrote novels, novellas, short stories, and poetry. He was, at various times in his life, a shepherd in Patagonia, a stevedore2 in Buenos Aires, a student at Princeton, a professor at the Iowa Writers Workshop, a writer in exile who spent time around Barcelona. He won numerous awards for his work—was twice a Guggenheim Fellow, won Chile’s National Literature Prize, and the William Faulkner Foundation Prize, and many more.

The Latin American Boom is characterized, in part, by a focus on politics—coinciding with the Cuban revolution’s impact on South and Central America, the coup that put Pinochet in power in Chile, guerrilla warfare after the fall of Perón in Argentina. Communication between countries across Latin America was increasing, the middle class was experiencing a “coming of age” as cities and suburbs grew, and the US and Europe began paying attention to not only the region’s politics but to its culture, its writers, etc.

Stylistically, the authors of this literary movement rejected the social realism they would have encountered in literature they read growing up. In their works, language becomes less formal and rigid; chronology is often intricate and nonlinear; and multiple perspectives and voices mingle and merge across a single work.

But Donoso felt, and declared himself, to be kind of adjacent to the Boom writers, working alongside them but not entirely as one of them. Although so many of his works navigate class divides, politics, labor, rural-urban disparities, Donoso didn’t feel as though he was setting out to write about politics, rather the political emerged from the personal. Additionally, some of these feelings of “otherness” could have stemmed from periods of illness Donoso underwent, but also likely from his homosexuality. During his life, Donoso remained closeted and married to a woman, despite tentative public speculation. Open discussion of his queerness took place only after his death in 1996.

Hell Has No Limits, one of Donoso’s early novels3, is brilliantly cinematic even at just 163 pages.4 I was surprised by how sucked into Estación El Olivo I became, how real it felt, a Chilean olive-growing town beginning to fall into ruin and fade away.5 There’s electricity in nearby villages and cities, but not here. Business has been stuttering to a halt, windows shuttering. Families and workers are moving away.

Donoso’s cast is dynamic and compelling: he writes menacing characters, underdog characters, and plenty of morally ambiguous characters. Our protagonist is La Manuela, a transgender sex worker who runs a brothel with her daughter. Pancho Vega is a scheming, embittered truck driver who’s back in town and bee-lining for revenge at La Manuela’s front door. There’s the outwardly benevolent local politician and landowner to keep your eye on, Don Alejo, with his sly gentleman’s white mustache. There are also neighbors, cousins, children, workers, a terrifying trio of dogs, and the looming ghosts of childhood friends. La Manuela’s daughter is strange and stern and captivating; her late mother, La Manuela’s former business partner, is a fascinating puzzle.

The prose moves between characters’ perspectives, and from third-person into first and back again, into and out of memory, across identities, between timelines; reading was a daydream-turned-feverdream-turned-nightmare. And when things get dark, it feels as if there’s no off ramp: cause barrels downhill into effect at a terrifying pace. Donoso is now, thankfully, officially on my radar, and I’m looking forward to picking up more of his work very soon.

Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin, tr. Bonnie Huie (New York Review Books, 1994/2017)

Notes of a Crocodile was the only one of these three novels familiar to me before seeing it on Moore’s seminar syllabus. That striking NYRB cover is hard to miss, and the novel’s cult status—on social media and especially amid LGBTQ+ readers—is undeniable. Qiu was Taiwan’s first prominent lesbian writer6 at the time of the publication of this book, her debut novel, in the mid-90s. She later moved to Paris to pursue a graduate education in psychology, feminism, and philosophy. It feels remiss not to include that Qiu died by suicide just one year after Crocodile’s publication and shortly after writing her epistolary sophomore novel Last Words from Montmartre.

Notes of a Crocodile takes the shape of a series of journals written by the narrator, a university student nicknamed Lazi. The journals alternate with surreal episodes that feature humanoid crocodiles, or crocodiles wearing human suits, who live among humans in Taiwan and are the often unwitting subjects of sensational tabloid news.

Qiu’s prose includes descriptions and turns of phrase I’d never come across before and am confident I won’t ever read again. Sometimes you’re reading and feel so deeply in another’s mind that you interpret the world around you as they might, for better or worse, inhabiting their moods, their perspectives, and their personal philosophies on the relationships they do or don’t have. Lazi’s perspective is occasionally overwhelming, always intense. Yet even in the novel’s most difficult moments, it felt worthwhile to see the world through this narrator’s eyes. I have no doubt translator Bonnie Huie’s talent contributed to the sharpness, liveliness, and sheer originality of the novel’s prose in English.

The originality I’m admiring here appears on all scales. At its smallest, I’m thinking of surprising similes. There’s a scene where Lazi is biking to catch up with her crush Shui Ling after a conflict and absence, and Qiu opens the chapter: “1989. Shui Ling. Gongguan Road. My Romantic Tragedy, round two.” She writes, and I can’t get this image out of my mind, “It felt as if my tears were absorbed by a giant bath towel before they could seep out, and there I was, as cheerful as ever.” What is it about the giant bath towel that’s so striking and sticky in my mind?

Lazi moves through relationships that serve her and those that don’t—all of which leave resounding impacts on her health and psyche. She’s careless, and she’s anxious; she’s harsh with others, and she’s striving for connection in whatever ways she knows how. In addition to the romances7, this book features some of the most distinct friendships I’ve recently read.

About fellow university student Zhi Rou, Lazi writes:

“The two of us had a certain rapport. There was an unspoken understanding that we would never cross over into the reality of each other’s lives, and our friendship took on a profound weight because of it. Careful to limit our interactions to chance encounters, we felt free to show affection and to speak whatever was on our minds, and those moments contained the makings of a great friendship.”

And I simply couldn’t pass up on the chance to share this quote about writing, which has come to mind time and time again in the weeks after having finished this novel:

“Sometimes writing was like finding a parking spot: Just as I was about to give up, I managed to achieve a perfect fit, thanks to a bit of skillful maneuvering. Other times it was like examining food that had been left sitting out for so long that ants and cockroaches had gotten to it. On other occasions it was like a major year-end cleaning where I was forced to throw something away because I couldn’t find anywhere to put it. And still other times, it was like trading in a used car for a new one: I didn’t give it a second thought.”

Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima tr. Meredith Weatherby (New Directions, 1958)

Playwright, filmmaker, and writer Yukio Mishima’s second novel8 Confessions of a Mask, feels split almost perfectly into two parts, despite being one whole from beginning to end. The first half covers narrator Kochan’s childhood and adolescence in Japan, his sexual awakening, his speculations regarding the origins of his fantasies (which feature violent death amid heroism; battlefield brutality and gore), his first crush (the “bad boy” in his class at school), and the conviction with which he begins “hypnotizing” himself into believing in his own so-called normalcy.

In the novel’s second half, World War II has broken out, and Kochan is conscripted but doesn’t face battle and is rather stationed in manufacturing and labor positions—and intermittently sent home for poor physical health, which has plagued him from his earliest years. He’s grown into an understanding of his urges and “shames” (read: his homosexuality), however far away the possibility of self-acceptance might still be. As a young adult, he begins a not-quite relationship with a good friend’s sister, Sonoko. Even after calling the relationship off when she and her family begin expecting an engagement, the two remain in touch. The narrator’s future rings bleak, despite the novel’s ambiguous conclusion. Here, too, I feel I have to mention that author Mishima’s life ended in ritual suicide when he was 45.

Thematically, I was struck by the strong presence of myth and fairy tale in the text, complete with imagery of dragon-slaying knights alongside religious icons and figures (incl. Saint Sebastian), all of which were formative in the narrator’s youth.9 In Mishima’s novel, fairytale imagery is almost always countered with ekphrastic writing on gore and violence—especially after the narrator has gained access to explicit wartime photographs. The intensity of the narrator’s childhood fantasies and visions were so startling to me, I think, because his fascination felt so contemporary; I found myself reading it against our contemporary concerns about violence in video games, for example, or fears about ready access to graphic videos and images on the internet, and so on.

In Confessions, wounds and injuries are so prevalent as to even appear in nonhuman description. In one scene, Mishima writes:

“The snow seemed like a dirty bandage hiding the open wounds of the city, hiding those irregular gashes of haphazard streets and torturous alleys, courtyards and occasional plots of bare ground, that form the only beauty to be found in the panorama of our cities.”

Another recurring descriptor that caught my attention throughout the novel: Everything seems to be glistening, gleaming, and glittering. Having noticed this pattern in the latter half of the book, I’d be eager to dive into another closer read to trace it through the text. On a quick flip-through in the meantime, I’m noticing that quasi-love interest Sonoko’s eyes “glisten” as they try to speak for her in a moment of silence. Characters’ white skin “gleams,” and their white teeth “gleam,” too. Especially when those characters are objects of the narrator’s (sexual) attention. He sees “glistening fatigue” in the faces of soldiers. When one is in a state of post-ejaculation, he notes, one “glitter[s] with debauched loneliness.” And finally, that last image of the novel [kind-of spoiler here!]: The narrator regrets having brought Sonoko to a grimy dance hall. His eyes train in on a tabletop across the room, upon which a beverage has spilled and now throws back “glittering, threatening reflections.”

How strange, to picture fatigue and loneliness as things that glitter and glisten. Strange, too, for “glittering” reflections to threaten. There’s a lightness to all those shimmering g-words; they glow and sparkle. They’re pretty, usually. But in Mishima’s work, they align with danger and despair. Why? I wonder if the gleaming and glittering indicate instead a remove from reality. Images become unreal, like the mirage of an oasis in a desert. The world around Kochan is untrustworthy, or false: a mirage itself. He’s constantly convincing himself of his reality, of his normalcy, yet he looks around and sees the gleam and glisten of mirrors reflecting back the truth of his sexuality, which he’s determined to deny. Even in his first memory, on the novel’s third page, the shaft of sunlight into which he’s been born “flickers”—or perhaps doesn’t exist at all.

“I had succeeded in hypnotizing myself. And from that time on, ninety percent of my life came to be governed by this autohypnosis, this irrational, idiotic, counterfeit hypnosis, which even I definitely knew to be counterfeit. It may well be wondered if there has ever been a person more given to credulity.”

In one of my favorite lines, Mishima writes, “There came a day in late spring that was like a tailor’s sample cut from a bolt of summer, or like a dress rehearsal for the coming season.”

He writes, “Everyone says that life is a stage. But most people do not seem to become obsessed with the idea, at any rate not as early as I did.” And later:

“My ‘act’ has ended by becoming an integral part of my nature, I told myself. It’s no longer an act. My knowledge that I am masquerading as a normal person has even corroded whatever of normality I originally possessed, ending by making me tell myself over and over again that it too was nothing but a pretense at normality. To say it another way, I’m becoming the sort of person who can’t believe in anything except the counterfeit.”

I’d love to know what translated and/or queer lit you’ve read or are looking forward to reading. I’m eager to pick up Eva Baltasar’s Permafrost (tr. Julia Sanches), the first in her Boulder trilogy, which has been on my shelf for far too long for me not to have gotten around to it.

If you’re looking for more…

Princeton houses much of José Donoso’s archive, and you can flip through many of his notebooks on their digital site here! He has very beautiful handwriting, and I wish I knew Spanish. His scrapbook of newspaper clippings is very endearing.

You can read an excerpt from Notes of a Crocodile here at Words Without Borders.

& more newsletters I’ve written on literature in translation:

Taught by the very amazing Michael F. Moore, who translates from the Italian

A dock worker who loads and unloads ships

A bit of trivia: this book was actually adapted into a movie in Mexico in 1978, by dir. Arturo Ripstein, and it was selected by Mexico to be their submission the Academy Awards’ foreign film category that year (although wasn’t chosen). Reception was critical at the time: one review declares “socially significant for a country obsessed with virility, but it is so badly designed and directed that it ruins its potential; for all its visual impact it might have been photographed through linoleum and the clumsy climax provoked hoots of hilarity.”

Since then, though, it’s become a bit of a cult hit and was screened at the Venice Film festival in 2018. You can watch the trailer on Youtube here.

A Radiator Springs-style disappearance

She was a filmmaker and artist as well

Which we may, today—and back then—consider variations of toxic (although Qiu and Huie are commendably and sufficiently nonjudgemental)

Long speculated to be memoir/autobiography, at least in part

We also read Italian writer Mario Desiati’s Spatriati in the course, in which a young queer man spends a good amount of time in the church, and in a short interview over Zoom, Desiati wondered aloud why statues of Jesus are always so naked and so traditionally attractive

I am sold by the sound of Hell has no limits!! Enjoyed reading your Notes of a Crocodile review - I found that so hard to review because of how singular it is.. it is so hard to evaluate, without spoiling it, or just describing it.

This was such a beautifully curated list. I love how you spotlight queer classics in translation and bring attention to works that might otherwise be overlooked. Thanks for sharing these thoughtful recommendations!