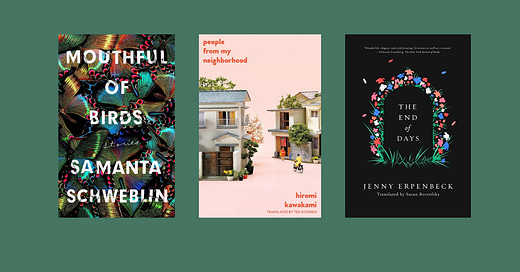

My Women in Translation Month Wrap-Up (Pt. 1)

In the first half of August, I read 3 books from Argentina, Japan, and Germany

Regan’s newsletter publishes biweekly book recommendations on a theme. Subscribe, and you’ll find 3 new book recs in your inbox every other Friday. Past newsletters have covered the Memoir-in-Essays, the Cure for Autofiction, Summer Reading, and more.

In my beginning-of-August newsletter, I recommended three novels in translation by women authors to celebrate the start of Women in Translation Month; I also committed to reading translated books by women writers for the entirety of August.1 This week’s newsletter includes the first three I’ve read—two story collections and one novel-in-parts. You can expect another newsletter in your inbox next Friday featuring the three works of translated literature I’ve read / am reading in August’s second half.

I’ve been reflecting quite a bit recently on why I’m drawn to translated literature and might develop and articulate some of my thoughts in my next letter—but for now, here are three recommendations: a macabre collection of short fiction set in South America; fantastical tales about the inhabitants of a Japanese neighborhood; and a haunting, human story through eras of German history.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin, tr. Megan McDowell (Riverhead, 2019)

Argentinian author Samanta Schweblin’s feminist horror stories are gritty, grimy, and strange. Four of her books are available in English, three of which have been long- or short-listed for the International Booker Prize. Fever Dream won a Shirley Jackson Award, and Seven Empty Houses won a National Book Award. All have been translated by Megan McDowell, who, at an event I covered for my college news site a few years ago, called Schweblin a “master of suspense.” In one of my favorite parts of the talk, McDowell described the way she sets the atmosphere for translating Schweblin’s fiction (and Mariana Enríquez’s, another Argentinian horror writer):2

When Megan McDowell is getting ready to translate horror, she reads the opening paragraph of The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson. She focuses on its music, dreaminess, and precise adjectives; the words Jackson uses to describe the physicality of the house can also describe the gothic novel’s theme of morality.

McDowell emphasizes that, as a translator, it’s important to think about what words say but also about how they sound and how they resonate.

Mouthful of Birds features 20 stories. While a few are longer, many stories are crisp, concept-driven flash pieces with last-sentence twists. They’re about an adolescent girl who eats live birds, a field of abandoned brides, a merman, and more—all occurring in the eerie, suspenseful atmosphere between dream and reality.3 Her stories weave around themes of labor and class (“The Digger”, “Toward Happy Civilization”), violence and its futility (“Irman”, “The Test”), the art world (“Heads Against Concrete”, “The Heavy Suitcase of Benavides”), and flawed family relationships—especially parent/child (“The Size of Things”, “A Great Effort”)—to name just a few.

The stories all managed to grab my attention and hold my interest. Some were surprising and others methodical—but few felt 100% complete to me, able to pull me in entirely, which, more than anything, has motivated me to pick up one of Schweblin’s novels, which I think I’ll love even more.

People From My Neighborhood by Hiromi Kawakami, tr. Ted Goossen (Soft Skull Press, 2021)

Hiromi Kawakami is one of Japan’s most popular contemporary novelists, and in the Anglophone world, she’s probably best-known for her novel Strange Weather in Tokyo, the translation of which came out in 2013. Like Samanta Schweblin’s, Hiromi Kawakami’s short fiction takes unexpected, surreal turns. But where Schweblin’s prose is dark and suspenseful, People From My Neighborhood operates on a more whimsical, fantastical level (though often no less unsettling). I agree with translator Ted Goossen that the stories are “written in a deceptively simple way. In fact, it’s that style that gives the stories their special power,” which he says in this wonderful interview.4

The 26 short stories in People From My Neighborhood (which are often just three or four pages long) follow the inhabitants of a single neighborhood: the new families moving in, elderly familiar faces, the strangers passing through. These fragments move through time, and often characters reappear, like the middle-aged woman who runs a bar called the Love, a “dog school principal,” and the young girl Kanae, the narrator’s closest friend, who, at other times, plays the role of next-door delinquent.

Classic interconnected story collections like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio and Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine also build mosaics of small-town life by jumping from one inhabitant to the next. What distinguishes Kawakami’s work is the way rumor and mythology infuse everyday occurrences, complete with ghosts, illnesses that turn people into pigeons, memory manipulation, and magical wishes.5

The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky (New Directions, 2014)

I read my first novel by Jenny Erpenbeck, Go, Went, Gone, in a German literature course about“borderlands,” and I’ve loved all that I’ve read by her since. Erpenbeck has written four novels, a novella, a memoir, and a story collection, all of which can be found in English translation. Her most recent, Kairos, won this year’s International Booker Prize.

The End of Days is built out of five “books”; each explores the same woman's life and the alternate tracks it could have taken. This isn’t a spoiler—since it's the concept of the novel—but at the end of each book / story, the main character dies at a different age. Between each story is a brief “intermezzo” that goes something like “if x hadn't happened, and if y had gone differently, then maybe…” after which the reader is pulled into the next story. The main character is a bit older, now, and she's in the midst of an entirely different moment in German history.

The End of Days reminded me of Erpenbeck's Visitation, which follows a house on a Brandenburg lake6 and its ever-changing inhabitants over the course of more than a century, from the late 1800s into the Weimar era, through both World Wars and eventually to the fall of the GDR and its aftermath. The End of Days follows almost this exact timeline through German history. On the other hand, I feel like the novels Go, Went, Gone and Kairos are also a pair that fits nicely together; each is more traditionally narrative and steeped in one cultural moment / era rather than spanning decades in a formally more experimental way. Go, Went, Gone is about the refugee crisis of the 2010s, and Kairos is set in the GDR just before (and during) the fall of the Berlin Wall.7

Erpenbeck’s prose in The End of Days has a slow, deliberate musicality that required my full focus, and as a result, I felt like I was moving through the stories in slow motion. But the novel crescendos in a really magnificent (and expectedly tragic) way that made me want to start again from the beginning (I cried).

From Book IV: “Time has blurred all those things that happened for the last time without it being called the last time. At some point her mother had pinned up her hair for her for the last time while her sister sat at the kitchen table doing her homework. At some point she sat in Krasni Mak for the last time. At many points during her life she had done something for the last time without knowing it. Did that mean that death was not a moment but a front, one that was as long as life? And so was she tumbling not only out of this world, but out of all possible worlds? Was she tumbling out of Vienna, out of Prague and Moscow, out of Berlin, out of the Socialist sister countries and the western world? Tumbling out of the entire world, out of all the time there ever was, would be, is?”

And one more passage, I can’t help myself, from Book III:

“Sometimes she would take her father’s glasses off his nose to clean them. She and her friend had sometimes stood side by side, comparing their legs. Once she had lain awake all night long beside her friend’s fiancé, weeping. For Comrade G. she had sliced through an entire stack of paper at one go. Before she kissed her husband for the first time, she grabbed him by his shock of hair, pulling him toward her. Was she ever even the same person? Were there any two moments in her life when she was comparable to herself? Was the whole not the truth? Or was everything treason? If the person who is to read this account remains faceless to her, what face should she be showing him? Which is the right face for a blank mirror?”

Thanks for reading! If you’re looking for more…

I love this interview between Xiao Yue Shan at Asymptote and Susan Bernofsky (who translated the Jenny Erpenbeck novel above!), which came out on the journal’s blog yesterday. The interview is about Bernofsky’s new translation of Yoko Tawada’s novel Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel. Tawada writes in Japanese and German, and Bernofsky has translated many of her German books. I recommended one of Tawada’s novels originally written in Japanese in my most recent newsletter.

Martha, who writes the Substack Martha’s Monthly, put together a really great Women in Translation Month newsletter featuring her ten favorites from the past year. I wholeheartedly agree with her recommendation of Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament, and I’m adding Cousins by Aurora Venturinito and The Details by Ia Genberg to my to-read list.

I did also listen to the audiobook for Headshot, which was not translated and takes place in Nevada and is very good—but more on Bullwinkel’s Booker-longlisted debut in a future newsletter.

Please bear with me as I copy & paste from my own article

The stories in Kim Fu’s collection Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century have a very similar uncanny, unsettled tone. I’d absolutely recommend it if you’re already a fan of Mouthful of Birds.

My favorite excerpt from the Goossen interview:

“As for models, I didn’t have any specific English text in mind, but one is certainly relevant: E.B. White’s classic children’s novel, Charlotte’s Web. For the last year, I have been living with my two-and-a-half-year-old grandson. He loves being read to, so I have revisited many of the books of my own childhood. E.B. White was an editor at the New Yorker, the “guardian” of American literary style, and in fact Charlotte’s Web is beautifully written. The writing flows smoothly, without any excess ornamentation, in a style that never calls attention to itself. As a result, it can be enjoyed by both parents and children alike. Though the contents of Kawakami’s Neighborhood are not always suitable for children (“Baseball” comes to mind!), the way the stories are written can be enjoyed by even the very young – just ask my grandson, who has heard many of them (his favourite is “Pigeonitis,” especially when the reader acts it out!)”

Though more fragmentary than Haruki Murakami’s short fiction, Hiromi Kawakami’s stories and their casual instances of magical realism reminded me of his work. Translator Ted Goossen’s name was familiar to me, and it only took moments before it clicked—that I’ve also read his translations Murakami in the collection Men Without Women and craft memoir Novelist as a Vocation.

Based on Erpenbeck’s grandparents’ home outside of Berlin!

I’m eager to read Erpenbeck’s novella The Book of Words, set in an unnamed South American country, her memoir Not a Novel, and her story collection The Old Child.

I love McDowell and all she translates so I am sat for the ‘Mouthful of Birds’ rec! I’m planning my October reads rn to include some Jackson and Enriquez’s ‘Our Share Of The Night’ so that makes me excited!

I’m intrigued by the Erpenbeck rec - my first of hers was Kairos this year and to be frank, I hated it. A lot of people in the translated lit lover community really adore her, so I am unsure if I should try again w a different novel! What would you recommend? I would also love to read your thoughts on why you’re drawn to translated lit - I think about it all the time too, and have written various pieces about it but never put any of those thoughts in a newsletter.

And thank you for sharing my piece! I look forward to you reading Cousins & The Details xxx