Bookshelf Tarot

When and why we decide to pick up certain books, and what they tell us (3 recs & a new biweekly series)

In London this January, I made my way through rainy Marylebone to Daunt Books, where, on the main display table, a stack of slim paperbacks caught my attention with a pink-purple pattern like geometric clouds. I opened Thomas Gardner’s Poverty Creek Journal1, and my eyes fell to the following, from Lisa McInerney’s introduction to the just-published 10-year anniversary edition:

“It’s easy to ascribe to fate finding the right book at the right time—the book that answers the question that’s been needling. But I think, instead, we’re drawn to specific topics, experiences or accounts; that finding the right book is an active event, rather than circumstance. We pick from the shelf the book that demands our attention. We open the page that we want to read.”

It’s uncanny how I so often seem to read the right book at exactly the right time. How, had I read any one book a year earlier or a few months later, the impact would have been entirely different. What pulls a title or author into your subconscious and prompts you to seek it out, then to begin reading?

An adage in marketing and publicity says a consumer needs to see or hear about a book seven times before deciding to buy it—a friend’s recommendation, a bookstore display, an online ad, a social media post, etc.—which I don’t think feels totally true, but there’s certainly truth in it: myriad factors nudge us toward our next read. A connect-the-dots type of kismet.

When I was a kid—as a slumber party game, or on my own—I’d pull chapter books from my shelf at random and ask questions about the future as if I were looking into a Magic 8 Ball. I’d turn to any page, close my eyes, and press my pointer finger to a paragraph or line; and there, I’d find my answer. It’s lucky, I think, that reading still feels this way to me today.

Recommending 3 books I happened to read at the right time

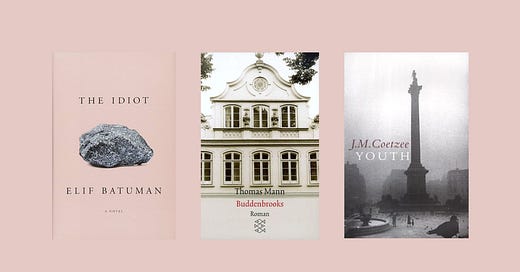

The Idiot by Elif Batuman (Penguin Press, 2017)

In the years after its publication, reading Batuman’s coming-of-age novel about Turkish American narrator Selin’s first year at Harvard seemed quickly to have become a rite of passage for the liberal arts-educated 20-something, and its popularity produced in me that push-pull of wondering whether I’d like it as much as I wanted to, or expected to.

Last fall, I moved to a very small town next to a medium-small town on the outskirts of Hamburg, Germany, and I was spending lots of time running 10k laps around the lake behind my new home. The audiobook was available on Libby and narrated by the author. The time felt right, I hoped the book would be good company, and it was.

The Idiot is witty, dry, heartfelt, and often hilarious. Selin is naive, intellectual, and built from an awkward, endearing combination of sincerity and apathy. She learns Russian, makes friends (Svetlana!), falls in love, and then—I had no idea—joins a program to teach English in Hungary come summer. This June marks the final leg of my ten months teaching English abroad, and Selin’s bizarre experiences, laments, reflections on purpose (did she have one?) already felt familiar, just weeks after my move.

Batuman wrote a first draft of what would become The Idiot, about her first year of college, in her early 20s. Only after a PhD in comp lit and a career in journalism did she pull out the manuscript, discover there was in fact some merit and truth in her juvenilia, and give it the sweetly ironic title of The Idiot, a play on the Russian literature her main character studies, and, well, her main character.2

Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann (S. Fischer, 1902)

In my final semester of undergrad, five classmates, my professor, and I read Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks week by week, meeting every Tuesday to discuss plot developments and drink coffee, just as much like old friends in a book club as young academics in a senior seminar. The 800-page German classic was Mann’s debut (before his more recognizable The Magic Mountain), and it earned him the Nobel Prize in 1929.

Buddenbrooks follows three generations of a 19th-Century merchant family in the Northern German city of Lübeck. Mann modeled the novel’s youngest character on himself: Hanno, the final bearer of the Buddenbrook name. Tony, an opinionated young woman central to the novel, takes after Mann’s aunt. Industrious Thomas, after Mann’s father.

That senior spring, I decided to enroll in a short summer course at the University of Kiel3. Out of a handful of programs across Germany, it was Kiel’s proximity to Lübeck that honestly caught my eye. I could visit Mann’s hometown, even his historic family house, coined the Buddenbrookhaus.4 It was due to my month in Kiel that I ranked states in Northern Germany highly in my teaching grant application; which is to say, it was Thomas Mann who led me to the Dorf in which I’m writing this newsletter.

Last October, I chaperoned a 12th-grade geology class field trip to the Baltic spa town Travemünde, where, in Buddenbrook’s third part (my favorite), Tony falls in love for the first time, reiterating themes of free will, fate, and privilege. The seascape along clay cliffs was a romantic, muted blue, and shrouded in fog.

Youth by J. M. Coetzee (Secker, 2002)

The second installment of Coetzee’s “fictionalized memoir” had been on my to-read list for years. Articles circulating about his most recent collection, The Pole, had brought him back to mind. And on the day I discovered a little free library across from my favorite cafe, a worn copy Youth was the only English title across four shelves.

Youth follows a young man who leaves the unrest of South Africa in the 60s for London. In my mind, it’s a sort of cautionary parable. Coetzee’s narrator wants to be a poet with an artistic, fulfilling bohemian life, but this all seems just outside his grasp through no fault of his own; he’s obsessed with his “unchangeable nature,” which widens the divide between his current and ideal selves. He “kills time while waiting for his destiny to arrive.”

Coetzee’s narrator gets a practical job as a computer programmer out of necessity. He realizes, “What more is required than a kind of stupid, insensitive doggedness, as lover, as writer, together with a readiness to fail and fail again? What is wrong with him is that he is not prepared to fail.” More importantly, “He has stopped yearning… Does it mean he is growing up? Is that what growing up amounts to: growing out of yearning, of passion, of all intensities of the soul?”

Coetzee writes with an amusing, ironic distance I can’t help but liken to Batuman’s The Idiot. Similarly, at its core, Youth is a deeply honest and innocent story of desire, longing, and probably also tenderness. But it's also about all the ways the narrator gets in his own way and is unable—or unwilling—to see beyond his inhibitions.

I’m always eager to talk / write / read about books, so I’m excited to be working on this new series of mini-recommendations on a theme. The plan is to send newsletters out biweekly, so you’ll be seeing the second installment in early June, with the theme “The Cure for Autofiction.”

If you’re looking for more in the meantime…

Two columns I’ve loved reading recently (which, clearly, inspired this little project): the NYT’s Read Like the Wind column by Molly Young (and guests) and The New Yorker staff writers’ Wednesday series The Best Books We Read This Week

Since German author Jenny Erpenbeck and translator Michael Hofmann won the International Booker Prize earlier this week (!), I wanted to share links to my two favorite essays on Kairos from the past year: by Alexander Wells and Ross Benjamin for The Baffler and The Point, and another on GDR nonfiction by Lizzy Kinch for Verso.

I ended up buying and loving Poverty Creek Journal, a 52-part work of prose / poetry / diary by a professor, runner, and writer who kept a journal to reflect on his runs over the course of 2012, which also became the year his brother unexpectedly passed. About grief, nature, family, solitude, craft, spirituality, and so on.

I also listened to The Idiot’s sequel, Either/Or, about Selin’s sophomore year at Harvard. And recently, Batuman sold and announced the next two releases in what will now be a four-book Selin series: the third installment takes place when Selin is in her 20s and 30s in California, and the fourth when she publishes her first book at 40.

Capital city of Germany’s northernmost state, Schleswig-Holstein, which borders Denmark, the North Sea, and the Baltic

I came to learn, staring up at its facade (and the large notice on its front door) in 2022 and again in 2024, that the Buddenbrookhaus will be under renovation until 2029.